By Susan Dreyer Leon

This weekend, five of us from the Mindfulness for Educators Certificate program presented at the annual conference of The Association for Contemplative Mind in Higher Education Conference. The title of our presentation was “Mindfulness and Reflection: Tools for clarity, creativity and compassion.” The students in the program did a beautiful job of describing how they have been using the frameworks of the program to deepen their own practice in their classrooms and with their students. I also had a chance to talk about one of the mindfulness practices were are using here at Antioch New England and I’ve included that here for your perusal! We are still accepting applications for the Mindfulness for Educators Certificate Program for 2012. Join us!!

The benefits of a simple practice

The Integrated Learning Program at Antioch University New England is an M.Ed with Elementary Certification. We begin our required course sequence with a Human Development course. This course takes as its text Robert Kegan’s The Evolving Self, which leads our students to discoveries about elementary- aged children and themselves. Three years ago, after some scattered practice of mindfulness meditation in different courses in the program, the faculty agreed that all sections of Human Development would begin their weekly Friday morning class meeting with a simple meditation. The meditation was developed by AUNE Adjunct Faculty, Besty Taylor and Integrated Learning Program Director and Core Faculty, Jane Miller. The full text of the meditation below.

Benefit for the course instructors: Clarity

I’m a better instructor because of our mindfulness time at the beginning of class. Clearing my head before we begin with course material makes me clearer in MY teaching. The jumble of things I want to cover settles out and I find myself being sharper in my focus. –AUNE instructor

My tendency in class it to talk too much. The “stop” of this arriving meditation gives me time to connect with my intention to limit my own airtime, listen from my heart and not so much my brain and make that listening my mindfulness practice in class. What emerges is often a much clearer articulation of the course content and a sparkling, surprising incisiveness in my ability to connect that content to students’ lives. –AUNE instructor

Benefit for the students during the class meeting: Clarity & Compassion

This practice gives students in the Antioch teacher preparation program an opportunity to feel an interruption in a fast paced day. Their future classrooms will be busy, hectic at times. They’ll be making dozens of decisions every hour. Our hope at Antioch is that they’ll remember what it was like to stop the speedy flow and have a time out. –AUNE Instructor

One student commented that this mindfulness practice that we have “is like a power nap. I feel refreshed afterward.” Another said, “I came in a snit and now I feel like I love you all.” Refreshed, kind teachers are what our graduates want to be and we need to support them in finding the tools to be that. One tool is mindfulness. –AUNE students & their instructor

Transitions cause my mind to race in a million different directions. This gives me a chance to just be, to clear the chalkboard in my mind. –AUNE Student

It constantly brought me back into awareness of my own humanity in a time of great demand. –AUNE Student

Benefit for teachers-in-training: Compassion

Mindfulness practice has helped me better understand and attend to behavior issues in the classroom. –AUNE Student

Unhurried, undistracted attentiveness is what teachers need in order to observe their students carefully, to know them well and understand how each one is making sense in the world. We talk about “meeting our children where they are” but, really, we can only do that if we SEE them, are attentive to them. Our five minutes of mindfulness is a time to practice unhurried, undistracted attentive awareness. –AUNE instructor

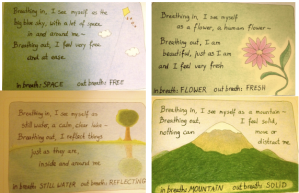

A meditation for arriving

by Betsy Taylor and Jane Miller, Antioch University New England

There’s something I’d like to do with you in this course that has to do with being present—not thinking of what you’ll be doing later or about what went on earlier but really be in in the moment—It’s an important skill for teachers, and for all people.

I’d like us to spend 5 minutes now practicing being present—to really arrive here—do a simple kind of meditation—no religious connections—purely a way to be here and mindful.

I’ll lead us but if it feels better to you to use this time to think or rest, that’s O.K Either close your eyes or find a soft focus on something. Begin by focusing your attention on sound. Don’t try to hard to go out and find sound.Let it come to you (you may notice sounds in the room: chair scraping, coughing. You may notice sounds in the building around us. You may notice sounds of your own body as you breathe or swallow)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~Silence~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Now, letting the awareness of you body move into the background, be aware of any emotions you’re experiencing—excitement, nervousness, irritation, frustration—just notice without judgment.

Now bring your attention to being aware of the movements of your breath. Soften around the waist. Notice as you breathe in the lungs fill up with air and the diaphragm pushes down notice if there is movement in the abdomenBe aware of breaking in. Be aware of breathing out. Observe the body as it breathes. Use awareness of the breath as a way to be really present in this moment

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~Silence~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

When you notice your mind wandering, as it will, very gently escort your attention back to the breath

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~Silence~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Open your eyes. Look around the room. Notice what you see. (maybe light and shadows, colors, maybe textures). Now look around at each other.

And with this arriving, our class is ready to begin!